VASECA is a research project in which I intend to map, describe, interpret and publish about the use of various kinds of vases (kantharos, chalice, amphora, etc.) as a symbol in christian art. The focus of this research is on the period from the 3rd through the 7th century.

Author and owner of the project: Jan Piebe Tjepkema. All photographs are mine, unless mentioned otherwise.

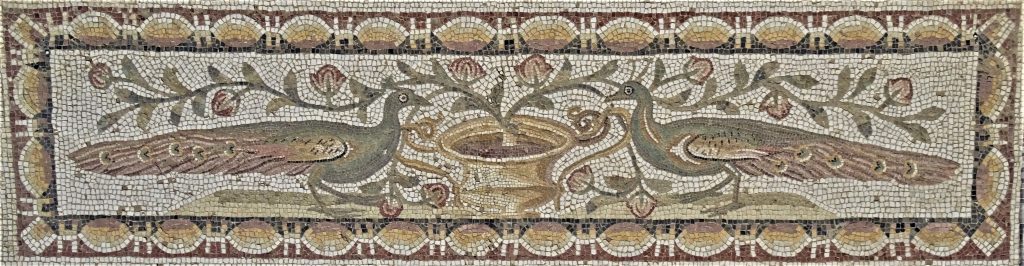

This, for instance, is a floormosaic in front of the altar area in a 6th century church in Bulla Regia. Today this is an excavation area in northwest Tunisia, famous for its underground houses with mosaicfloors. In those days it was an important town in Roman North-Africa, having several churches. In the mosaic, of the opus tesselatum type, a kantharos, originally a cup for drinking wine, is placed between two peacocks. This symbol represents the belief in a happy afterlife. Apparantly it was thought to be useful to remind the faithful of this belief when they were involved in the rites at the altar. The symbol of antithetical peacocks on either side of a kantharos is, however, not an exclusively christian symbol, as can be acknowledged in El Jem, a town towards the southeast of Tunisia famous for having the largest Roman arena of Africa. There you can see the symbol, in mosaic form, on the threshold of a room in the so-called Maison d’Africa, clearly in a non-christian context.

In the 4th century the symbol of peacocks and kantharos was used almost simultaneously in non-christian and christian graves in Viminacium, a Roman garrison-town at the Danube river, in present day eastern Serbia. In the cemetery here, with many graves from the 3rd till 6th century, graves were often covered by a kind of hip roof made of stone slabs decorated on the inside. Whether such a grave was for a christian or a non-christian person can often be derived from the context, for instance whether or not a Chi-Rho (Christ)-monogram has been painted somewhere. So here the excavators found a grave considered as non-christian with a peacock and kantharos painted on both long sides of the cover:

From more or less the same period is a grave with peacocks on both sides of a kantharos which is considered christian, because on the other short side a chi-rho monogram has been painted.

Findings as these from Viminacium, today displayed in the Archeaological museum in Pozharevac, confirm the otherwise wellknown facts that, in the first place, much symbolism applied in early christian art was not unique to early christian culture but derived from the cultural surroundings in which christianity developed; and second, that the christian belief in a, hopefully happy, afterlife was not unique to the christian religion. The investigation of vase symbolism in early christian art thus underlines the fact that the development of the christian religion in its early centuries did not pose a fully radical breach with the predecessing culture, but that it constituted, at least partly, a fluent adaptation to pre-existing religious beliefs and cultural expressions. This is an important historical aspect of the VASECA-project.